News

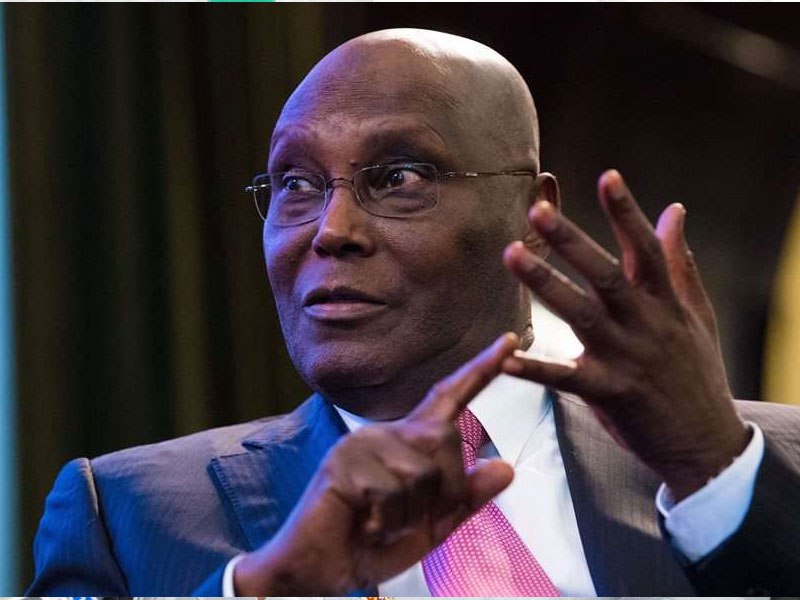

Just In: Cash Distribution Will Never Combat Poverty – Atiku

Jennifer Akamanu

The presidential candidate of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), Atiku Abubakar, does not think direct cash distribution to the poor can help combat poverty, as he takes a different policy path to President Muhammadu Buhari on addressing the malaise.

The Buhari administration has a string of special intervention programmes operated to tackle poverty, a scourge that has taken a soaring nature in Nigeria, ironically Africa’s largest economy by GDP size and largest oil producer.

According to the World Bank 2017 Atlas of Sustainable Development Goals, between 1990 and 2013, Nigeria added 35 million people to its poverty population, jumping from 51 million to 86 million (and now over 100 million). Of the 10 populous countries surveyed, Nigeria is the only country that failed to reduce poverty.

By 2018, Nigeria has overtaken China and is only behind India, arguably, with the highest number of extremely poor people within one national territory.

Among the Buhari anti-poverty programmes, Trader Moni offers N10,000 cash to market women (and men) trading in a few markets across the country. There is also a N5,000 monthly grant to ‘poorest Nigerians’. The latter does not offer up to $1 a day to the beneficiaries, falling below the $1.9/day global poverty line.

“Rather than direct cash distribution,” says Mr Abubakar in the policy document he launched at the start of the campaign towards the 2019 elections on Monday, “What we shall do (is to) provide skill acquisition opportunities and enterprise development for job and wealth creation (and) improve citizens’ access to basic infrastructure services – water, sanitation, power, education and health care.”

He also vows he would help “marginalised and vulnerable citizens” remove discrimination and enhance their access to education and income-generating activities as well as “implement pro-poor policies that will enhance their participation in economic activities and improve household income.”

Ultimately, Mr Abubakar, a former vice-president, promises to lift 50 million people out of poverty by 2025. To execute this ambition, there are no specifics or mentioning of the steps to be taken in Mr Abubakar’s policy document.

Instead, the PDP candidate says he would “reconcile the link between economic growth and human development through proper selection of effective polices on education and health, and set as our major policy objective the transformation of the agricultural sector into a viable high-income generating enterprise for the rural workers.”

But in social media event to kick off his campaign, he mentioned it would take two years to achieve the goal of removing 50 million Nigerians from poverty.

He spoke of “investments (that) will create a minimum of 2.5 million jobs annually and lift at least 50 million people from poverty in the first two years.”

“If he says creating 2.5 million jobs would lift 50 million people out of poverty, that is almost impossible to achieve given that Nigeria’s average household is about five or six persons,” economist Mohammed Al-Salafi said, pointing to flaws in Mr Atiku’s policy ambition. “So we could expect to see about 15 million people who would benefit from that policy, assuming it comes to fruition.”

Meanwhile, one other programme of the current All Progressives Congress (APC) administration, N-Power, is not about direct cash distribution. It deploys thousands of unemployed graduates to fill inadequacies in public services in education, health and civic education, with N30,000 monthly benefit. It is the country’s poster work-for-cash social programme to address the challenge of unemployment.

However, it comes short of fitting into the standard definition of conditional cash transfer (CCT), contrary to the government’s boasts.

CCT programmes transfer cash to poor households based on the condition that the beneficiaries demonstrate pre-specified investments in the human capital of the members of the households, especially children.

In other words, they are not just for the recipients to use for clothing and feeding, but also to combat wider effects of poverty and social problems a country faces such as low-school enrolment rate, poor rate of vaccinations for children, gender disparities and malnutrition, among others.

For instance, in Bangladesh and Cambodia, CCTs have been used to drive a reduction in gender disparities in education, the World Bank reports.

In the case of Nigeria, however, there are no conditions that beneficiaries of social programmes need to demonstrate; for instance, enrolling their children in school – to tackle the country’s notorious problem of high number of children out of school.

At any rate, Mr Abubakar’s current plan does not get to grips with the gaps in the current administration’s policy and consequently offers no remedy.